Why Are We Still Using Guidelines From the 1980s to Treat Today’s Moms?

With outdated postpartum blood pressure guidelines failing new parents, researchers like Dr. Emily Rosenfeld are working to close the gap in postpartum care.

It’s peculiar that, in 2025, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) continues to base its guidelines for postpartum blood pressure treatment on a single study of just 67 participants, published nearly four decades ago in 1987. During the postpartum period, a new parent’s blood pressure can quietly spike to life-threatening levels. Yet despite evolving standards in cardiovascular care, the two primary postpartum hypertensive disorders, preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, are still treated using this outdated guideline.

Dr. Emily Rosenfeld, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, wants to change that.

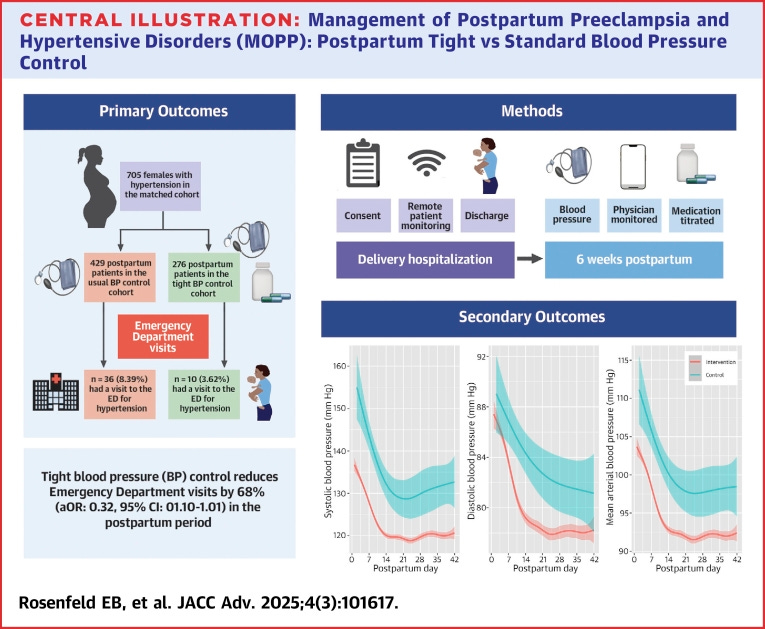

In a study published earlier this year, Dr. Rosenfeld and her colleagues took the blood pressure recommendations for non-pregnant populations—the levels suggested by the American Heart Association—and applied them to nearly 400 postpartum patients instead of using the ranges offered by the ACOG. The result was a significant decrease in emergency room visits for postpartum patients with a hypertensive disorder. Rosenfeld also employed remote patient monitoring, which allowed her to receive real-time updates on her patients’ blood pressure, catch any rises immediately, and then adjust their medication to prevent someone from entering a hypertensive crisis.

In a field where maternal mortality rates—especially among Black women—remain unacceptably high, relying on such an outdated and limited evidence base raises serious questions about institutional inertia, research priorities, and the systemic undervaluing of women’s health.

The current political context is also crucial to consider. The Trump Administration is increasingly attacking public health research as a whole. Funding for public health research is being slashed, and entire areas of inquiry are stigmatized or de facto blocked. In this climate, the failure to update clinical guidelines with current data presents as a symptom of a broader devaluation of science, particularly when it comes to the lives of women, birthing people, and marginalized communities.

In this interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, Dr. Rosenfeld explains how remote tech enabled faster interventions and why tighter control of postpartum blood pressure will save lives.

Julia Craven: Before we get too deep, what is tight blood pressure control, and how is it beneficial for patients?

Dr. Rosenfeld: Tighter blood pressure control is when we lower a patient’s blood pressure once it starts to creep up and before it gets to a dangerous threshold. By targeting tighter blood pressure control, we do a better job of keeping patients out of that really dangerous zone where they end up having seizures, brain bleeds, and other complications.

Okay, awesome. Tell me about your work and how it inspired this study on tighter blood pressure control for postpartum patients.

I recently completed my maternal fetal medicine fellowship at Rutgers. I have always been interested in and passionate about addressing disparities and improving birthing people’s health. Overall, I think pregnancy is a special time because it's when people who usually aren't engaged in the healthcare system are very engaged. It's an opportunity to impact someone's health for the rest of their life.

During my fellowship, I recognized that people were having to come back to the emergency department for hypertensive disorders, and this was something that impacted mother-infant bonding, breastfeeding, mental health, and it's really expensive. And so, in thinking about how we can better treat birthing people postpartum, I looked at the guidelines and realized that the guidelines for managing blood pressure postpartum were developed in the 1980s. It was based on a really old study of only 67 patients. It got me thinking: Why are we still doing something that isn't working when we have updated these guidelines outside of pregnancy? And maybe by reevaluating how we treat patients, we can make it safer for Black and other birthing people in the United States. That's how we came up with the idea of taking the guidelines currently used for non-pregnant patients and using them for our postpartum patients.

Unfortunately, the ACOG guidelines are not shocking, but they gave me a lot of pause. Sixty-seven people are a small study, even within the realm of small studies. Why is that problematic for determining the blood pressure guidelines that are applied to postpartum patients, especially considering that they’re still used today?

That study, published in 1987, looked at a handful of patients with high blood pressure and said that most people recover within four to six days postpartum and that only patients with blood pressure above 150/100 don't tend to recover.

But we’re dealing with a different population than we were almost 40 years ago because our patients are giving birth later, meaning they're older. They're oftentimes more obese, have preexisting hypertension, and overall, they are sicker. So, just because someone’s blood pressure is 140/90 when they go home doesn’t mean that it’s not going to go up to a dangerous range when they're at home. We saw that pretty consistently throughout the study, where 75 percent of patients enrolled required a medication adjustment in their first week postpartum, and not all of them had preeclampsia; some had gestational hypertension.

For Black women, the leading causes of death in the pre- and postpartum periods are preeclampsia and eclampsia—the latter of which is marked by seizures, which can potentially be followed by a coma, in a pregnant person. Could you give a rundown of why blood pressure control helps keep people from developing this condition, and how the condition affects the human body for people who may not be familiar with preeclampsia or eclampsia, and how that can end a pregnant person's life?

Preeclampsia impacts about two to eight percent of all pregnancies. It starts early in pregnancy, and we think it happens because the placenta does not develop properly. The pregnancy essentially outgrows the blood flow of the placenta, which releases a bunch of basically inflammatory markers that, as the pregnancy continues to develop, end up causing the complication. Now, when these blood pressures are really high, your brain can’t tolerate them, and you can have neurological symptoms. If this is not treated, then there's a risk of seizures. There are also risks of blood vessels in the brain bursting. The liver can also be impacted where a hematoma, basically a collection of blood, can form in the liver, and if that ruptures, that can be deadly. Patients can get blood clots all over their body, and that can lead to internal bleeding that can be devastating for the pregnant person as well as the fetus or the newborn.

Luckily, we do have a lot of resources and things to prevent it from getting to that point. But that requires proper identification of preeclampsia, which is sadly missed in some cases. It also requires engagement of the patient with the healthcare system—and there are a number of barriers to that happening.

There used to be an opinion that patients may have had a genetic predisposition to developing preeclampsia at a higher rate. The newer thinking that I subscribe to as well is that it's not that there's a genetic difference or a predisposition, it's that there's stressors of systemic racism and stressors in the life that Black birthing people are more likely to face that leads them to have a higher susceptibility to adverse events like preeclampsia. So it's the stress of the system itself that hasn't always been as supportive of Black birthing people as it should be that causes those changes in the body. There is data that patients are sometimes dismissed at a higher rate. Their problems aren't addressed based on their race or ethnicity.

This is a health tech newsletter, and I noticed while reading that you used remote monitoring for patients. Can you tell me more about that?

The remote patient monitoring that we employed allows blood pressure to be sent to my cell phone at all hours of the day. It’s an opportunity for the healthcare system to allow for more touchpoints in the postpartum period and overcome many barriers to coming in for a postpartum visit, like transportation, childcare, and all of those additional barriers to interacting with the healthcare system postpartum.

There was no way for me to capture this in the study, and I probably should have thought of a better way to do this, but a lot of the Black patients I enrolled were scared. They were scared of preeclampsia, they were scared to go home because of the things that they've seen in the news and experienced in prior pregnancies, or heard from friends or family. They would tell me that they were grateful to have remote patient monitoring because they felt like they weren't alone at home, and it made them feel safer.

That is fantastic. This isn’t an equitable experience, but I had a pre-diabetes scare, and I wore a Stelo for a few weeks. Knowing where my blood sugar was at all times just made me feel better.

Exactly. The hospital system got a grant, so we had a bunch of blood pressure cuffs that came with tablets, like iPads. So monitoring didn't use the patient's cell phone, it didn't use their data, it didn't require their wifi. When the patient took their blood pressure, it would come right to me, and I would either text or call them or send them a message through the electronic medical records to say, “Hey, your blood pressure's a little high, why don't you repeat it?”

Based on that blood pressure reading, I would tell them to start, stop, or change medications, and I could do that in real time. So it wasn't like your blood pressure's high, you have to call the office. The office tells you to repeat it, and then you repeat it, and you call back, and then they have to page the doctor to get the answer. It allowed things to happen in real time and allowed me to basically micromanage everyone's blood pressure.

So, since you were doing this in real time, you were able to adjust their medication virtually, and they could go pick it up?

Yeah. We would start them on medication in the hospital, and then, if they needed it, I would prescribe new medication as needed.

That’s so dope. Based on what you found in this study, what are some potential solutions to help people better manage their blood pressure postpartum?

The biggest one is that it is safe to be more aggressive with blood pressure management, and that we can safely target a lower blood pressure. Obstetricians can get nervous about making someone's blood pressure too low because we know it peaks at days four to six postpartum, and then it slowly goes down, but that drop is slow. I've found with managing nearly 400 patients, it's really hard to bottom someone out and make their blood pressure too low.

Now, when people are considering whether or not to start medication in the postpartum period, there is data that suggests that it will benefit the birthing person and it's safe.