How to Cure Your Anxiety About Aging

My new essay, featured in Prism, is the marquee piece of September's Living A Better Life Resources.

A fun fact about me is that aging has never scared me. I wrote about this increasingly rare perspective for Prism and am featuring a snippet of it—plus a little extra—as part of this month’s Living a Better Life Resources.

Let’s get into it, shall we?

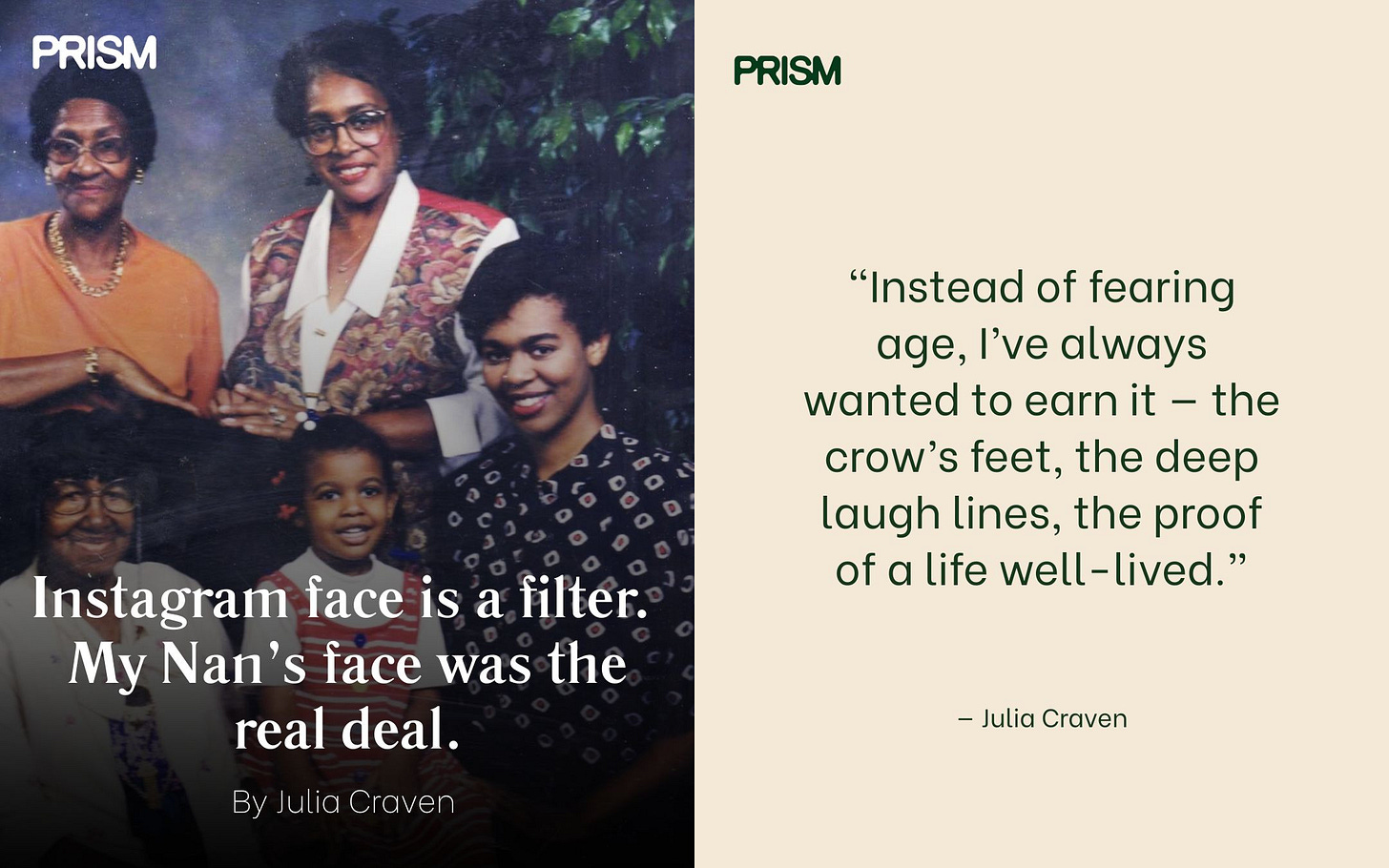

Instagram face is a filter. My Nan’s face was the real deal.

I’m not worried about how I’ll look when I’m older. I grew up surrounded by four generations of women whose beauty only got better with age — faces etched by laughter and late nights, not botox and fillers. Their lines told stories. Their loosened skin carried decades of living. They’d been here a while, and it showed in the best way. There was my great-great-grandma Vinnie; my great-grandmother, nicknamed Muss; my Nana; my Mama; and me.

Instead of fearing age, I’ve always wanted to earn it — the crow’s feet, the deep laugh lines, the proof of a life well-lived. Research backs this up: studies show young people with strong intergenerational connections have a more positive perception of aging, in others and themselves. Muss was my primary caregiver, and I also spent most afternoons with my Nana. I’d watch them — and my great-great-grandmother — do their hair and makeup, highlighting what they loved about their faces.

Only 20% of Americans live near extended family. You can see the fallout in how we view aging. Today’s youth are sold “prejuvenation” — anti-aging routines for tweens, injectables for 20-somethings — like a moral imperative. I’ll be 33 this September, right in the demographic supposedly spiraling about getting older. Sure, I grew up with some anti-aging noise, but I also had a chorus of women ready to shut it down if I hinted at “fixing” my face. (To be fair, I mostly said it to mess with them — but I’m glad they took it seriously.)

That’s all you get on Healthy Futures. Click the button below to read the full essay on Prism!

Why is our society so obsessed with flawlessness?

During the hours I spent working on this essay, this was the question I kept coming back to. I landed on the short answer being capitalism and how overexposed we are to each other online. The research and writing process reminded me of when I interviewed journalist Elise Hu, who wrote the book Flawless: Lessons in Looks and Culture From the K-Beauty Capital, in 2023 for an episode of The Waves. We had an extensive conversation about lookism1 and how it is intricately interwoven with the brute force of late-stage capitalism—along with the commodification of, well, everything.

Julia: All of this struck me as very capitalistic, especially the ideal face, since you have to conform if you want to acquire capital, which is another time suck. But we see this parallel broadly; we see it in Korea, the U.S., and other countries. What does this say about our society's desire for ownership over well-being?

Elise: This is the neoliberal dream: the idea that you can make yourself some sort of entrepreneur and that you're completely self-reliant—if you spend enough money [or] if you do enough consuming of whatever's in the market to improve yourself.

You're buying, and you're consuming, at the same time, you are also being consumed by society as an object. And I found that South Korea lives out the very ideals that America also tries to export all over the globe in a souped-up way. This is all tied to economic precariousness. This all came out of the 1997 financial crisis in South Korea, where unemployment skyrocketed. South Korea went bankrupt and had to pay back billions of dollars in loans from the International Monetary Fund. So the government sought other economic engines.

And one of those was the Hallyu wave2, which was banking on visuals, banking on exporting K-pop, K-drama, and K-culture in general. And then, with the exporting of those visuals, you also exported Korean aesthetics and beauty ideals. When they did that, they were also exporting and advertising plastic surgery and lasers and wands and facials and cosmetics and skincare in order to get there. So this was all part of a project to try and pay back an IMF loan originally. But the entire society got caught up in it because then everybody's trying to compete—not just on how educated they are or how capable they are for the job market, but with their outer self.

We have conflated good looks with morality, and we've conflated good looks with working hard, such that if you don't fit in... then somehow you're considered lazy or incompetent.

So, how does this align with social anxiety about aging?

If good looks—i.e., a youthful appearance—are equated with morality, productivity, and worth, then growing older and looking it becomes a failure. The body and face are treated as projects that must be constantly “managed,” bought into, and optimized to remain valuable. Looking at it this way, it’s easier to understand how aging is a blow to the neoliberal and conservative fantasies of endless self-improvement.

… And the current media landscape amplifies this conundrum.

When Instagram launched in late 2010, the feed was dominated by poorly color-filtered images of non-aesthetic dinner plates, grainy sunsets, and duck-lipless selfies—often in black and white and shot from an awkward, upward diagonal angle. By the end of the decade, it was more monotonous. It settled into the Instagram Face aesthetic, which New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino described as a composite of impossible features: poreless skin, high cheekbones, plump lips, a tiny nose, and exaggerated eyes. But, generally speaking, participating in this contemporary, IRL reboot of Number 12 Looks Just Like You was still somewhat niche.

That is not the case today.

This hyper-curated aesthetic has become a widespread standard, from the polished faces of TikTok influencers in their early twenties to reality stars on shows like Love Island and Selling Sunset. It’s particularly alarming in a world where we’re already so disconnected from our bodies. We spend significant time online, constantly comparing ourselves to curated images of others and meticulously curating our own. The emotional and mental impact here is concerning, especially in adolescents. While an urge to “fix” one’s appearance isn’t new, it does seem to start younger than it did in previous generations. Young people today are coming of age in a culture that treats visible aging as a problem to fix preemptively, pushing tweens toward costly anti-aging routines and people in their 20s and 30s toward cosmetic procedures designed for people at least two decades older.

What kind of relationship can you have with yourself if you constantly strive to manage or optimize your reflection?

What’s the solution here?

Community Is The Cure

As with many things, being in community is essential to improving this complex relationship with getting older. Intergenerational bonds remind us that beauty, wisdom, and value are not diminished with age but transformed. When we live near our elders, listen to their stories, and witness their lives unfolding over time, we inherit a different model of what it means to grow older—one rooted in care and connection rather than fear.

That’s the work in front of us: seek out and nurture those connections where we can. Call your grandparents or any other older family member if they’re still with us. Ask your neighbor about her life as you help her with her groceries.

Dismantling the fear of aging on a cultural level necessitates rewriting deeply ingrained narratives about beauty, worth, and visibility. Still, we can examine the sources of these fears—ads, influencers, and the casual comments we make about ourselves and each other—and question whether they should sway our self-image.

Journaling can also be helpful. Imagine your life at 70 or 80 or 90. Instead of focusing on limitations, write about what you hope your life will look like. What are your routines? How do you spend your days? What makes you happy? What do your friendships look like?

We can also be more intentional about the faces we celebrate, the stories we tell about beauty, and the beauty content we consume and support.

Some examples:

Recently, beauty brand Tower 28 tapped TikTok creator Jada Jones, who’s healing from topical steroid withdrawal and shared all the gritty details about her journey online, for their new eyeshadow campaign.

Another brand, Topicals, consistently pulls models with acne scarring, hyperpigmentation, and other skin “flaws” to star in multi-format campaigns.

Some thought materials:

[PSA] Aging is not a crime, and looking youthful is not a reward.

by u/whatisfunemployment in SkincareAddiction

This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism by Ashton Applewhite

Perhaps most importantly, we can remind ourselves and the people around us, whenever necessary, that aging is not a flaw.

Reclaiming our power from the many capitalistic endeavors that enter our heads daily isn’t only about what we reject; it’s also about what we reclaim. We have the power to choose our influences. Instead of bugging out about smile lines, let's live more expansively by honoring what time gives us instead of fearing what it might take away.

The exclusion or mistreatment of someone because they aren’t considered conventionally attractive.

The Hallyu wave refers to how South Korean pop culture has become both an international phenomenon and a significant influence on global pop culture.

![The ‘Tyranny of Vanity’ [PAID]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!YK_y!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7f553812-652b-4703-a2ad-915826a0fcd3_800x600.png)