“The Uterus Collectors”

How the forced sterilization of Black women upheld centuries of racist medical praxis.

“During the 1970s, sterilization became the most rapidly growing form of birth control in the United States, rising from 200,000 cases in 1970 to over 700,000 in 1980. It was a common belief among Blacks in the South that Black women were routinely sterilized without their informed consent and for no valid medical reason. Teaching hospitals performed unnecessary hysterectomies on poor Black women as practice for their medical residents. This sort of abuse was so widespread in the South that these operations came to be known as “Mississippi appendectomies.” — Dorothy Roberts in Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty.

Click on the footnotes to see additional information for specific pieces of information. The title of today’s post is a quote from professor Eric D. Smaw’s work on the subject.

Permanent forced sterilization1 followed a wretched pattern for many Black women. She’d go into the hospital for a different issue and come home not knowing she’d received a tubal ligation or total hysterectomy.

“Some women were sterilized during Cesarean sections and never told; others were threatened with termination of welfare benefits2 or denial of medical care if they didn’t ‘consent’ to the procedure; others received unnecessary hysterectomies at teaching hospitals as practice for medical residents,” writes sociologist Lisa Wade for Ms. Magazine.

In the South, the transgression was so common it was referred to as a “Mississippi Appendectomy” — a phrase some researchers believe was coined, or at least popularized, by Fannie Lou Hamer, one of the most prominent voices within the Civil Rights Movement. But whoever came up with the phrase wasn’t far from how those committing the crime described it. A 1954 FAQ pamphlet published by North Carolina’s Eugenics Board, in response to the question of whether the procedure is dangerous, states: “No. It’s comparable to an operation for appendicitis.”3

The Mississippi Appendectomy was an offense with which Hamer was familiar. In 1961, a doctor in Sunflower County, Mississippi, performed an involuntary hysterectomy on Hamer during surgery to remove a uterine tumor. To make matters worse, Hamer didn’t even know this happened to her until she overheard people gossiping about it on the plantation where she worked. Later, during her time as an activist, Hamer estimated that 6 out of 10 Black women in Sunflower County were also victims of this violence.4 The transgression is what pushed Hamer into the Civil Rights Movement. And her willingness to share what happened to her gave “voice to thousands of Black women who had been victimized by doctors working for public health agencies but committed to advancing the aims of racial eugenicists.”

Seven years later, in 1968, 14-year-old Elaine Riddick was involuntarily sterilized after giving birth to her son. “They didn't have permission from me because I was too young, and my grandmother didn't understand what was going on,” Riddick told ABC News in 2011. “They said I was feebleminded; they said I would never be able to do anything for myself. I was a little bitty kid, and they cut me open like a hog.”

“I was raped twice—once by the perpetrator and once by the state of North Carolina.”

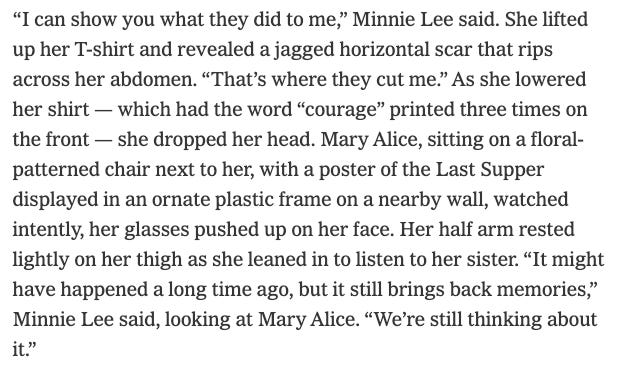

This history and its exposure to the general public is relatively recent, becoming widespread knowledge in the early 1970s following the forced sterilization of 14-year-old Minnie Lee Relf and her 12-year-old sister Mary Alice in Alabama. After receiving public benefits for the first time just months before, the two sisters were forcibly sterilized by a physician in a federally funded clinic in the summer of 1973. A lawsuit filed on behalf of the sisters by the Southern Poverty Law Center, Relf v. Weinberger, revealed that between 100,000 and 150,000 people who were living in poverty —half of whom were Black5, while the other 50 percent was mostly comprised of Latina and Indigenous women—were involuntarily sterilized under federally funded programs. The lawsuit resulted in a ruling prohibiting the use of federal funds for involuntary sterilizations and mandated that doctors obtain informed consent before performing sterilization. (Despite this, involuntary sterilizations would continue across the U.S. well into the 21st century.)

In this section from The Long Shadow of Eugenics in America, written by professor Linda Villarosa for the New York Times Magazine, the Relf sisters share the lasting effects of what happened to them:

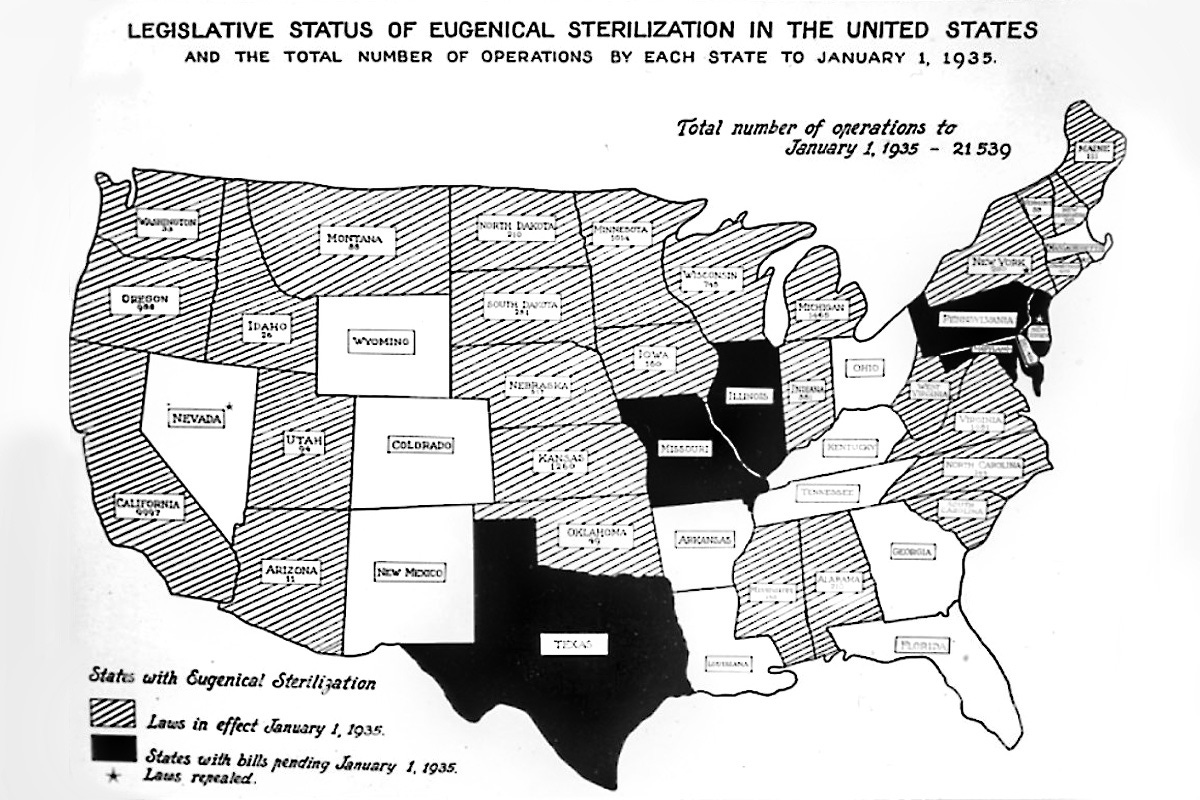

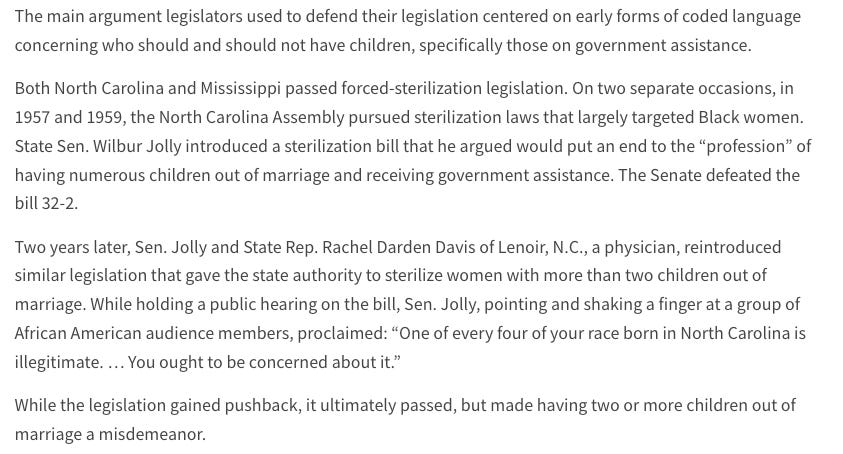

Hamer, Riddick, the Relf sisters, and many others were involuntarily sterilized after eugenics programs had lost much of their public repute in the U.S. following the atrocities of World War II in 19456. This is partly because the language shifted from physical attributes to racist socioeconomic ones as the Civil Rights Movement began. Southern politicians and clinicians saw codifying sterilization for “unwed mothers” with more than two children out of wedlock or those receiving public assistance as a legal means of maintaining white supremacy. Former Rep. Ben Owen of Columbus, Miss. described such policies as “the only way” to “stop this Black tide which threatens to engulf us.”

Here’s what a few others had to say:

“It is no coincidence that sterilization rates for Black women rose as desegregation got underway,” writes medical historian Alexandra Stern. “Until the 1950s, schools and hospitals in the U.S. were segregated by race, but integration threatened to break down Jim Crow apartheid. The backlash involved the reassertion of white supremacist control and racial hierarchies specifically through the control of Black reproduction and future Black lives by sterilization.”

As of February 2022, permanent forced sterilization is legal in 31 states and D.C.

The systemic determinations for the practice were designed to execute harm upon the most vulnerable in our society and prevent them from exercising agency over their bodies. The forced sterilizations of Black women are a legacy of enslavement that remains present today via medical mistrust, rational iatrophobia, racist clinical beliefs about Black people, and the dismissal of Black folks’ health concerns.

Annotations:

It’s imperative to know that Black women weren’t the only demographic subjected to forced sterilizations. The practice disproportionately affected Black, Latina, and Indigenous women. But people of all genders and races living in poverty, who are disabled, or anyone deemed “unfit to reproduce” by eugenicists were also subjected.

During the 1960s, “suitable home” policies became a prominent way for policymakers to make it harder to qualify for welfare benefits, according to research from Kenneth J. Neubeck and Noel A. Cazenave. The successor to these were “man-in-the-house” policies which prevented women recipients of welfare from receiving money from a man. Caseworkers would pop up at suspected homes in the middle of the night, a practice that disproportionately targeted Black women. If a man was thought to be living in the house—a definition that fluctuated with each caseworker—the woman’s benefits were threatened. In some cases, according to additional research by Tiffany D. Thomas and Mandy Hill, the women were offered forced sterilization in exchange for their benefits.

In some cases, doctors flat out told people they needed their appendix removed, according to research by Thomas and Hill. Clinicians would also falsify medical records to state that the procedure performed was an appendectomy or gall bladder removal, which hid the accurate number of forced sterilizations performed.

Medical historian Harriet Washington verified Hamer’s estimate in her book Medical Apartheid.

Per Thomas and Hill.

Ironically, Nazi Germany modeled their eugenics policies after those implemented in America. But, due to the “Hitlerisation” of eugenics, many Americans were no longer in favor of the widespread use of the programs.