What Do We Do With Products That Have A Racist History?

My alternative headline was, "What do we do with anything?"

When I planned out Salt + Yams’ editorial calendar for the year, it made sense for January’s theme to be Redefining the Glow Up, to push out stories within the newsletter’s scope that investigated the costs of self-improvement and shifted how we define “glowing up.” Example: Monthly facials are fun, and I’m not saying you shouldn’t get them, but, bestie, what if we also went to get a physical and complete blood panel?

I wanted to include a skincare post because it is both one of my favorite hobbies and a primary way people glow up—but I knew I wouldn’t like what I found. The truth is that we owe many of the Western world’s most significant medical discoveries to malpractice conducted upon people of color. In America, that demographic has historically been Black folks, those living in poverty, or disabled or incarcerated people. Many people treated inhumanely by medicine fall into all four categories.

Dr. Albert Kligman’s work in dermatology, which happened during his time as a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school, is a prime example of this. Many of you won’t recognize Kligman’s name, but his magnum opus is probably sitting on your bathroom counter.

In the late 1960s, he created a product that can only be accurately described as the Zeus of skincare: Tretinoin. Commonly known by its brand name, Retin-A, tretinoin improves acne, skin hyperpigmentation, rough skin, and sun damage and lessens the appearance of wrinkles and fine lines. Kligman’s other dermatological feats included treatments for scalp ringworm, alopecia, and giving the field scientific legitimacy.

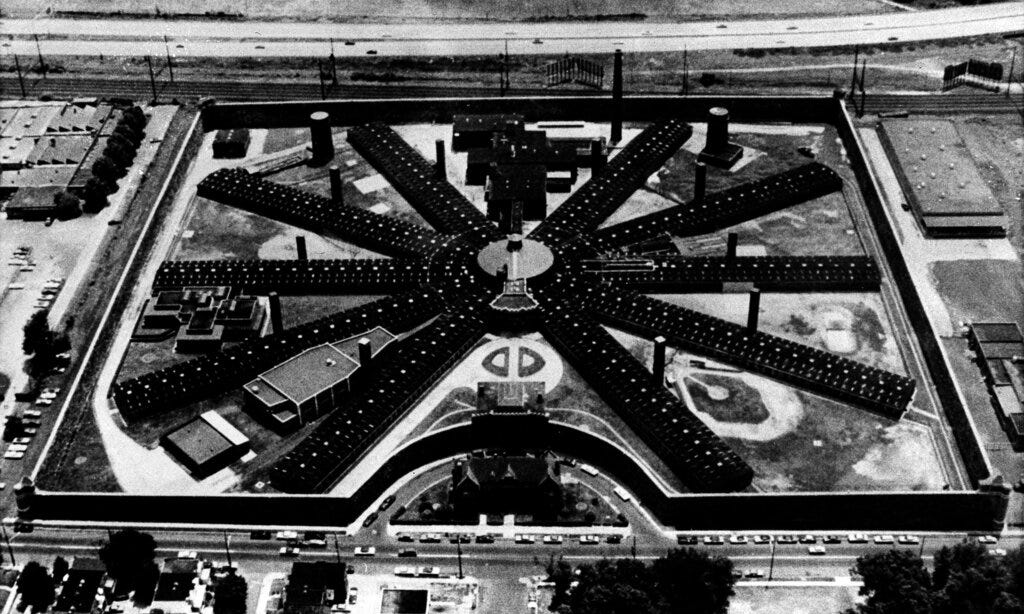

He achieved this through human experiments conducted on people incarcerated in Philadelphia’s Holmesburg Prison, most of them Black. Much of the information available on Kligman details his overzealous approach to harsh experimentation and his lack of remorse about it. Vitamin A is very irritating to the skin, so much so that physicians researching the acid during the 1950s and 1960s encouraged patients to use less of it. Kligman required incarcerated persons to keep using the medication.1

“He had that type of mentality—push on. Kligman was always pushing forward,” Dr. Chalmers Cornelius, one of the residents who worked under Kligman, told Allen Hornblum, author of Acres of Skin: Human Experiments at Holmesburg Prison2. Chapter Eight of Hornblum’s book dives into the harm caused to incarcerated people during the tretinoin experiments:

The early human trials were performed on the backs and faces of the Holmesburg inmates. As the university team tested for minimum and maximum dosage levels of different chemical compositions, the inmates suffered through the most dangerous, and certainly the most uncomfortable, phase of the clinical testing process. In a recent interview on the history of Retin-A® for Philadelphia Magazine, Kligman is quoted as saying that in the early stages he experimented with “very high doses” of vitamin A, so high that “I damn near killed people [before] I could see a real benefit… Every one of them got sick.” Kligman was experimenting with very high dosages, sometimes orally.3

For reference, the current prescription strengths of topical tretinoin creams range from 0.01 percent to 0.1 percent—which is significantly less than what Kligman used during the experiments. His human rights violations didn’t stop or start here. Here’s a summary of Kligman’s other work and his thinking about it from a 2020 editorial written by dermatologists Adewole Adamson and Jules Lipoff:

From the 1950s through the 1970s, as faculty at the University of Pennsylvania, Kligman led human subject research on prisoners, mostly African Americans with limited literacy. These inmates were primarily involved in cosmetic and pharmaceutical testing (e.g., tretinoin) but were also inoculated with infections and received biopsies and injections. The experiments included exposure to chemicals such as dioxin, a carcinogen and component of Agent Orange, which Kligman argued was too minimal an amount to cause harm.4 His other studies investigated radioactive and hallucinogenic compounds in partnership with government and pharmaceutical companies. Kligman published many studies detailing intentional inoculation of human subjects: herpes simplex and vaccinia virus, human papillomavirus, and Candida. He also infected children with mental disabilities with Microsporum audouini and Microsporum canis, causing tinea capitis.5 Many of these studies were conducted without formal ethical review, although formal ethical review did not begin in the US until the late 1960s and 1970s.

This history of experimentation on prisoners alone is troubling. In his own words to the Philadelphia Bulletin in 1966, Kligman described his first visit to Holmesburg Prison in 1951, when called to treat a fungal outbreak: “All I saw before me were acres of skin. It was like a farmer seeing a fertile field for the first time.”6 In reminiscing, it seems as though he saw prisoners as objects for experimentation. He also said, “It was years before the authorities knew that I was conducting various studies on prisoner volunteers. Things were simpler then. Informed consent was unheard of. No one asked me what I was doing. It was a wonderful time.”

The brutal experience of Yusef Anthony, a formerly incarcerated person who was experimented on, was written up in an article by The Daily Pennsylvanian, UPenn’s student newspaper.

Content warning: It is a graphic and candid explanation of the human rights violations he suffered.

Throughout his time at Holmesburg, Anthony underwent a wide array of tests that continue to affect his health over 50 years later. Patch tests on his back left him with chloracne—a collection of lesions and cysts on the skin caused by chemical exposure—and pus-swollen fingers and feet. In one trial, Anthony had to take a hallucinogenic drug and answer mathematical questions. In another test, he drank a milkshake that gave him hemorrhoids, forcing him to undergo operations to repair his damaged rectum.

Kligman, alongside Dow Chemical and Johnson and Johnson, two companies for which he conducted dermatological research, were sued in 2000 by nearly 300 formerly incarcerated people on whom the doctor experimented. The case was dismissed due to the statute of limitations being passed.

The doctor never expressed regret for his experiments, telling The New York Times four years before his death, “My view is that shutting the prison experiments down was a big mistake.” He added: “I’m on the medical ethics committee at Penn, and I still don’t see there having been anything wrong with what we were doing.”

I didn’t write this post with the intention of telling everyone who uses tretinoin or other skincare treatments Kligman discovered to throw it out, and that’s not my point now. I find that reaction to historic medical advancement unhelpful, a bit performative, and antithetical to my belief that we should focus on improving health outcomes. (My opinion on current malpractice is much, much different, but it’s also a whole nother post.)

Kligman falls in the same legacy of white male medical “genius” as James Marion Sims, a physician whose maiming of Black women contributed heavily to the development of modern gynecology. Sims’ legacy doesn’t mean people with female reproductive organs shouldn’t see a gynecologist—they should—just as Kligman’s legacy doesn’t mean you should stop using a medication that offers significant benefits to your skin. Clearing acne, hyperpigmentation, wrinkles, and other signs of aging can also improve mental health.

What we should do, however, is maintain a critical relationship with medicine and the products we consume. This relationship extends beyond the use of a product, or how much we like it, and hinges on understanding its history, the context of its development, the ethical considerations entwined in its creation, and acknowledging the harm caused to the people who made the product possible. And people affected—or their descendants if those directly harmed aren’t alive—should receive reparations.

Understanding the past and engaging thoughtfully with it helps us, at best, rework our society to stop heinous things from happening again or, at minimum, know what we’re looking at if the evils evolve and pop up in the present.

Hornblum, Allen M. Acres of skin human experiments at Holmesburg Prison. Hoboken: Routledge, 2012, page 212.

Hornblum, 213.

Hornblum, 212.

Kligman signed a contract with Dow Chemicals in 1966 to figure out the minimum amount of dioxin needed for a human skin reaction. Dow wanted Kligman to use between 0.2 and 16 micrograms, pretty small doses, of the chemical. Instead, Kligman used 7,500 micrograms, which gave the men lasting lesions, blackheads, and blisters. (Source: The Daily Pennsylvanian)

This is the clinical term for scalp ringworm.

This quote was the inspiration for the title of Hornblum’s book.